Despacito: Rate limiting protocol to mitigate DDoS attacks

Despacito (Spanish for “slowly”) is a vendor-neutral, rate limiting protocol to mitigate application layer DDoS attacks. It’s being designed by Relaycorp, with a view to proposing it as an Internet Draft (I-D). The purpose of this website is to gather feedback before writing an I-D.

Introduction

Despacito is a rate limiting protocol for Layer 7 reverse proxies (aka CDNs). It allows the origin server to provide the proxy with client information (e.g. user id, rate limits) and origin server state (e.g. current capacity), so that the proxy can decide whether to forward messages from any given client.

This effectively allows reverse proxies to implement rate limiting on a per-client basis, independently of the client’s IP address, thus complementing existing rate limiting mechanisms that are based on IP address reputation.

This protocol builds on the research we did for The DDoS Report. In fact, Despacito packages the following mitigation tactics into a coherent protocol, requiring minimal input from app developers and operators:

- Client authentication.

- Client-based rate limiting.

- Cryptographic challenges.

- Humanity verification.

- App attestation.

Despacito is meant to be pluggable. It may always be active, or activated on demand when the origin server is under heavy load due to an attack or a legitimate traffic spike.

To provide the proxy with information about the client, Despacito introduces a new component: an authorisation service, responsible for authenticating the client and, when authorisation is granted, issuing a short-lived certificate. This service may be offered by the origin server itself or a third party.

The client must use its certificate in all requests, as it contains most of the information that the proxy needs to make a decision.

Decision factors

The proxy will consider the following factors when evaluating an incoming message (e.g. HTTP request):

- The client’s identity per the certificate issued by the authorisation server. For example:

- Whether and how the client was authenticated. If authenticated, a unique client id and the underlying user’s id are included. The user id may be anonymised.

- Which cryptographic challenges the client solved, if any.

- Which humanity verification tests the client solved, if any.

- Whether the client software is trusted.

- The client’s rate limits (e.g. 5 requests per minute). Alternatively, we may let the proxy determine the rate limit from the other decision factors.

- The current capacity of the origin server,

as a float between 0.0 (idle) and 1.0 (at capacity), inclusive.

This could be provided by the origin server itself,

or the platform on which it’s running

(e.g. the

HorizontalPodAutoscalerin Kubernetes, serverless products like Google Cloud Run). For example, if the autoscaling configuration allows for a minimum of 0 and maximum of 10 instances, and there are currently 5 instances running, the capacity is 0.5. - The current threat level, as perceived by the operator of the origin server. For example, the operator might anticipate being the target of an attack in the aftermath of an event. The threat level is a float between 0.0 (no threat) and 1.0 (an attack is imminent), inclusive.

A fourth factor we’re considering is the “cost” of processing that particular type of incoming message. For example, an HTTP request to an endpoint that performs a computationally or financially expensive operation.

Possible outcomes

Based on the factors above, the proxy will take one of the following actions:

- Forward the request to the origin server.

- Challenge the client to go back to the authorisation server and request a new authorisation with enhanced credentials. This may also be caused by a change in the origin server’s capacity or threat level (we’re aiming to have a Time to Mitigation in the order of seconds).

- Reject the request with a

40Xstatus code, or equivalent in another Application Layer protocol. - Terminate the TCP connection if there’s a strong sign that the client is malicious, thus saving bandwidth.

Example

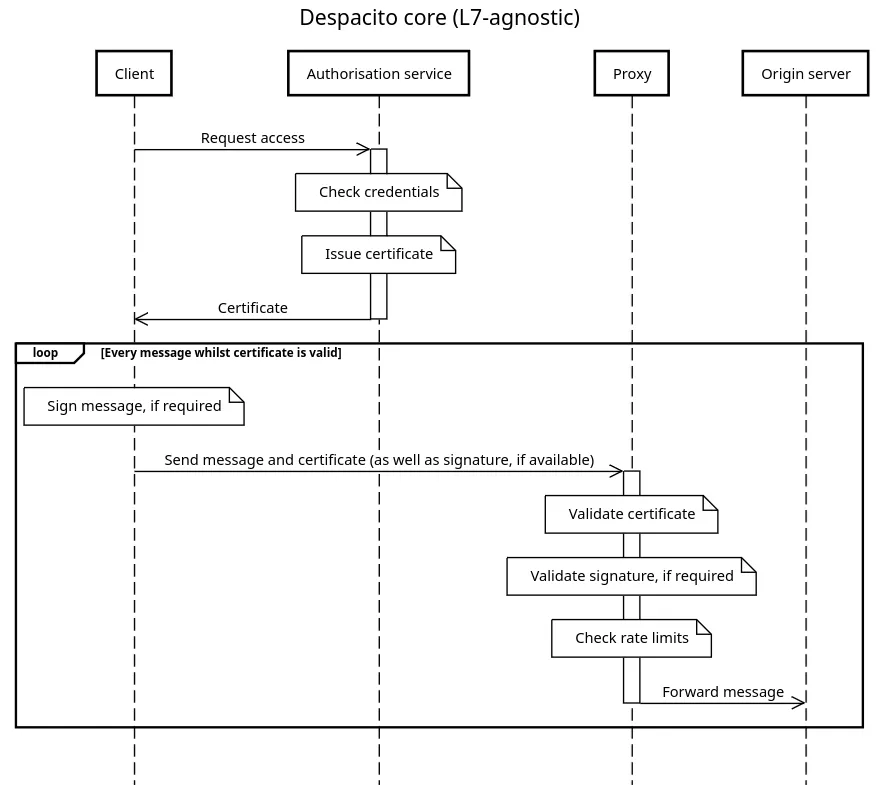

The following diagram shows a high-level view of the Despacito protocol when the client is allowed to communicate with the origin server.

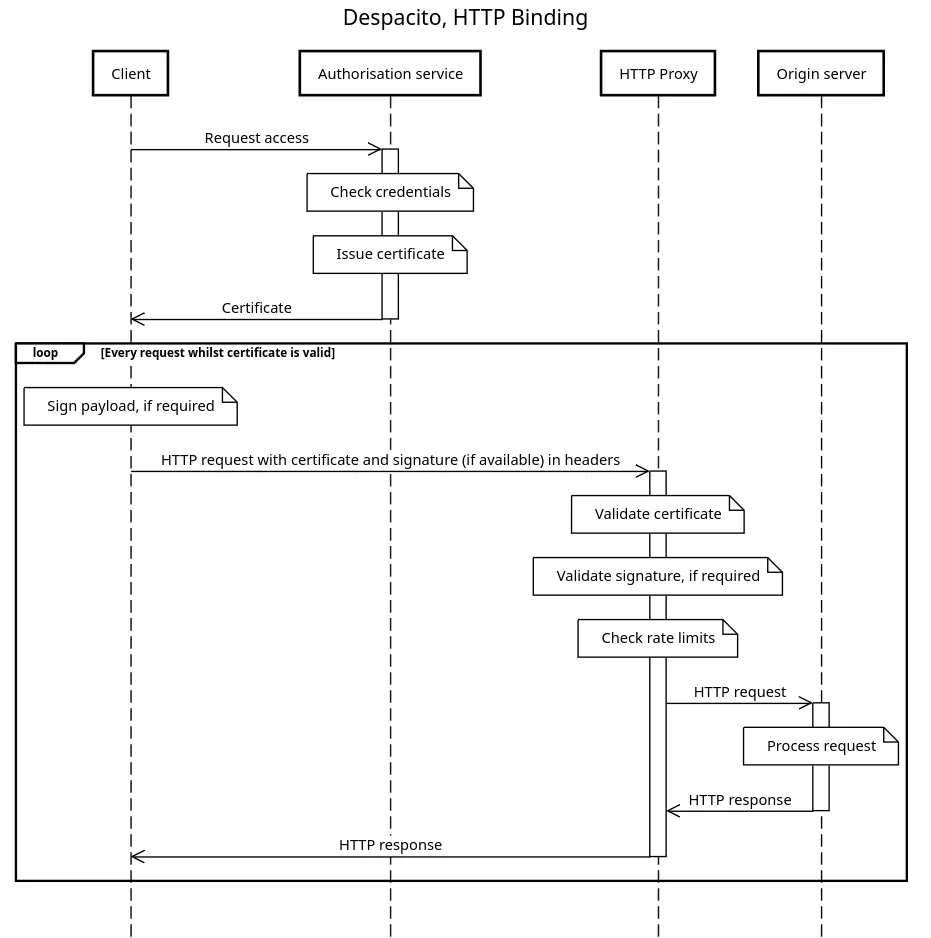

On the other hand, the following diagram shows the same scenario when using HTTP.

Collateral damage

Certain DDoS mitigation tactics, such as cryptographic challenges, can potentially be detrimental to the user experience and the environment if not properly implemented or configured. We should encourage developers and operators to adopt such tactics in an adaptive manner, proportional to the risk to the origin server.